The Joint Commission released a new hospital program fire drill requirement in surgical areas which detail specific drill elements in the December 2021 Prepublication Requirements[i]. This new requirement goes into effect in July 2022 and could bring greater scrutiny of your surgical area fire drills for these elements. Now is the time to review your current drill practices and ensure you meet the elements of the new requirement.

Surgical Fire Risk

Surgical fires occur 90 to 100 times each year in the United States according to recent data from the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI), an independent research organization[ii]. There is dispute among experts about how frequently these events occur with some experts indicating they may be up to six times the ECRI data. Regardless of the actual occurrences, it is believed these unthinkable events result in several dozen serious injuries and several deaths per year[iii].

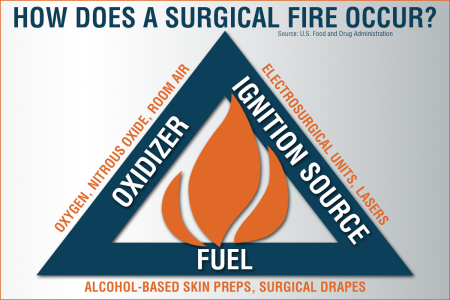

The risk of surgical fire could be considered greatest in the hospital environment given the combination of concentrated Oxidizers (nitrous/oxygen), Ignition Sources (Electrosurgical Units, Lasers, Drills, etc.) and Fuel (Alcohol-based Skin Preps, Drapes, Gowns, Gauze, Sponges, etc.). A review of operating room fire claims found that 85% of fires occurred in the head, neck, or upper chest which may guide considerations for prevention and drill scenarios[iv].

The New Requirements

The new fire drill requirements are under the Joint Commission Standard for Hospitals EC.02.03.03 EP 7. The expectations of performance are that hospitals that use aerosol germicides, antiseptics or flammable liquids in conjunction with electrosurgery, cautery, lasers, or other ignition sources, include:

- The hospital performs an annual fire drill in anesthetizing locations.

- The drill may be announced or unannounced.

- The drill addresses extinguishment of the patient, drapery, clothing, and equipment.

- Drill involves applicable staff and licensed independent practitioners.

- The focus on fire prevention.

- The drill includes simulated use of extinguishers and evacuation.

Organizations should conduct a risk assessment of their surgical practices to identify where the risk of surgical fire exists (use of flammable liquids coupled with ignition sources). A review of fire drills should be conducted to determine if these areas have participated in annual drills and if the measures of performance are aligned with the new requirements. Once this gap analysis is complete, organizations can implement their action plan to ensure compliance.

Prevention is Critical

The best response to surgical fires is to prevent them in the first place. When prevention fails, the surgical team must ensure it has a process to follow and has practiced it to perfection. According to the Food and Drug Administration[v], specific recommendations to reduce surgical fires include:

- A fire risk assessment at the beginning of each surgical procedure.

- Be aware the highest risk procedures involve an ignition source, delivery of supplemental oxygen, and use of an ignition source near the oxygen (e.g., head, neck, or upper chest surgery).

- Encourage communication among surgical team members.

- Ensure communication exists between the anesthesia professional delivering medical gases, the surgeon controlling the ignition source, and the operating room staff applying skin preparation agents and drapes.

- Safe use and administration of oxidizers.

- Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed for your patient.

- Any increase in oxygen concentration in the surgical field increases the chance of fire.

- At concentrations of approximately 30 percent, a spark or heat can ignite a fuel source.

- If supplemental oxygen is necessary, particularly for surgery in the head, neck, or upper chest area:

- Titrate to the minimum concentration of oxygen needed to maintain adequate oxygen saturation for your patient.

- When appropriate and possible, use a closed oxygen delivery system.

- If using an open delivery system, take additional precautions to exclude oxygen and flammable/combustible gases from the operative field, such as draping techniques that avoid accumulation of oxygen in the surgical field.

- Safe use of any devices that may serve as an ignition source.

- Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen (greater than 30 percent) are required.

- If an ignition source must be used, be aware that it is safer to do so after allowing time for the oxygen concentration in the room to decrease. It may take several minutes for a reduction of oxygen concentration in the area even after stopping the gas or lowering its concentration.

- Inspect all instruments for evidence of insulation failure (device, wires, and connections) prior to use. If any defects are found the device must not be used.

- In addition to serving as an ignition source, monopolar energy use can directly result in unintended patient burns from capacitive coupling and intra-operative insulation failure. If a monopolar electrosurgical unit is used:

- Do not activate when near or in contact with other instruments.

- Use a return electrode monitoring system.

- Tips of cautery instruments should be clean and free of char and tissue.

- When not in use, place ignition sources, such as ESUs, electrocautery devices, fiber-optic illumination light sources and lasers in a designated area away from the patient (e.g., in a holster or a safety cover) and not directly on the patient or surgical drapes.

- Recognize that other items that generate heat, including drills and burrs, argon beam coagulators, and fiber-optic illuminators, can also serve as potential ignition sources.

- Consider alternatives to using an ignition source for surgery of the head, neck, and upper chest if high concentrations of supplemental oxygen (greater than 30 percent) are required.

- Safe use of surgical suite items that may serve as a fuel source.

- Allow adequate drying time and prevent alcohol-based antiseptics from pooling during skin preparation and assess for pooling or other moisture to ensure dry conditions prior to draping.

- Use the appropriate size applicator for the surgical site. For example, do not use large (e.g., 26mL) applicators for head and neck cases.

- Be aware of other surgical suite items that may serve as a fuel source, including:

- Products that may trap oxygen, such as surgical drapes, towels, sponges, and gauze – even those which claim to be "flame-resistant."

- Products made of plastics including some endotracheal tubes, laryngeal masks, and suction catheters.

- Patient-related sources such as hair and gastrointestinal gases.

- Plan and practice how to manage a surgical fire. (DRILLS!)

- Stop the main source of ignition. Turn off the flow of flammable gas; unplug electrical devices that may be involved.

- Extinguish the fire –Use a safe method to smother the fire such as, water or saline, and a CO2 or other extinguisher if the fire persists.

- Remove all drapes and burning materials and assess for evidence of smoldering materials.

- For airway fires, disconnect the patient from the breathing circuit, and remove the tracheal tube.

- Review the fire scene and remove all possible sources of flammable materials.

- Evaluate if supplemental oxygen is needed for your patient.

Summary

Review of the new drill requirement and a comparison with your current practice will ensure that your staff are fully prepared to address any surgical fire event. Prevention is critical and reinforcing your surgical fire risk reduction efforts will need to be front and center in your patient safety practices.

[i] Prepublication Requirements. The Joint Commission. Released December 17, 2021. (Accessed March 13, 2022) https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/prepublications/hap_ec_edits_july_2022.pdf

[ii] ECRI Institute Announces New Initiative to Extinguish Surgical Fires. (June 5, 2018) https://www.ecri.org/press/ecri-institute-announces-new-initiative-to-extinguish-surgical-fires

[iii] Sentinel Event Alert 29. The Joint Commission. (Accessed March 13, 2022) https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_29.pdf

[iv] Operating Room Fires. Jones TS, Black IH, Robinson TN, Jones EL. Anesthesiology. March 2019, Vol. 130, 492–501.

[v] Recommendations to Reduce Surgical Fires and Related Patient Injury: FDA Safety Communication. (Accessed March 13, 2022) https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20191216153510/https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/recommendations-reduce-surgical-fires-and-related-patient-injury-fda-safety-communication

NFPA99 that covers Healthcare Facilities only recognizes Clean Agents & Water Mist fire extinguishers for operating rooms. Having been in the fire extinguisher industry for 33 years, we do not consider/recognize CO2 fire extinguishers as Clean Agent fire extinguishers. Also, they lower the oxygen levels below the limits that sustain life, and they can cause frostbite. It is my suggestion that you take the CO2 fire extinguisher referenced in the Plan and practice how to manage a surgical fire. (DRILLS!) section of this article and replace it with Clean Agent or Water Mist fire extinguishers.

Just my recommendation.

Thank you for your feedback, Steven. We appreciate it.

To what extent must the “simulate the use of extinguishers and evacuation” be taken to? Can an operating room technician verbally outline the use with a sel;ected extinguisher in hand? Does a bed physically have to be removed from the OR room?